Analog in-memory computing attention mechanism for fast and energy-efficient large language models

Store values in transistors, not bits

Analog in-memory computing attention mechanism for fast and energy-efficient large language models Leroux, N., Manea, PP., Sudarshan, C. et al. Nature Comput Science

The takeaway from this one is that there is a high cost to the synchronous digital logic abstraction.

Causal Attention Primer

Attention is one of the core building blocks of the Transformer architecture. During inference, the input activation matrix x is multiplied by 3 separate weight matrices to produce three intermediate matrices: Q, K, and V. Q and K are then multiplied together, scaled by a constant, and passed through a nonlinear activation function (e.g., softmax). This result is called an attention matrix A, which is multiplied by V.

Causal attention is a specialization which applies a mask to A. This restricts token i so that it can only attend to tokens <= i. This restriction enables the implementation of the KV cache.

KV Cache

The KV cache stores rows of the K and V matrices for later re-use. Say the network is producing output token i+1, there is no need to compute rows [0, 1, 2, … i] of K and V, they can simply be retrieved from the cache. Only row i+1 needs to be computed (and stored in the cache for future use). There is a nice animation showing a KV cache here.

Gain Cell

What follows next is a description of CMOS hardware which can both store values from K and V and perform the computations required by the attention mechanism. I feel a bit out of my depth, but here we go!

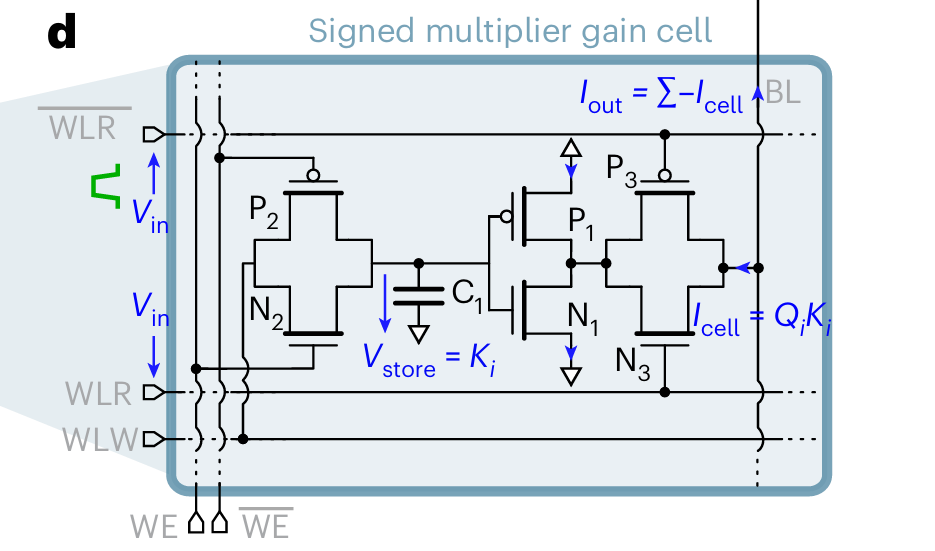

Fig. 1(d) shows a single gain cell (prior paper here). This single cell comprises a single capacitor and a handful of transistors.

The voltage of capacitor C1 represents a single weight value from K or V (not a bit in a floating-point representation of a number, but an actual real-valued weight). The WE and WLW pins allow the weight value to be updated. An element of Q arrives at a gain cell, represented by a pulse on the WLR pins. The width of the pulse is proportional to the value of the element; the amplitude of the pulse is a constant. For the duration of the input pulse, an output pulse is generated with an amplitude proportional to the voltage of capacitor C1. It’s been a while since I’ve had to compute an integral, but I think I can find the area under this curve. The total output current generated is:

input_pulse_width * capacitor_voltage

which is:

Q_value * K_or_V_value

The output currents of multiple gain cells are all dumped onto a shared bitline, and the aggregate current produced by all of them represents a dot product

Hard Sigmoid

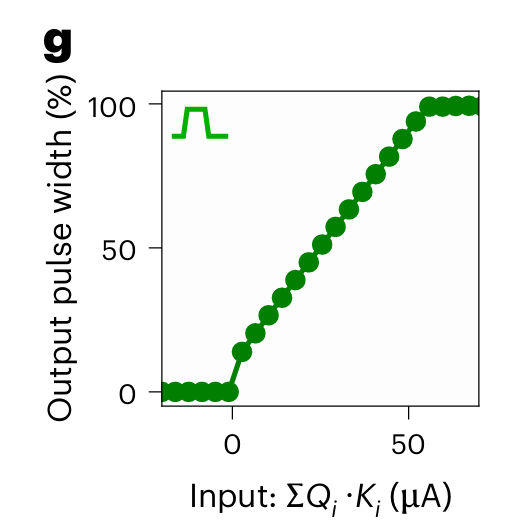

More analog hardware magic is used to produce a HardSigmoid charge-to-pulse circuit. It integrates all current received over the shared bitline, and produces a pulse whose width is a function of that current. Fig. 1(g) shows that function:

One gets the sense that this is not the ideal function from a machine learning point of view, but it is efficient to implement in hardware.

Sliding Window Attention

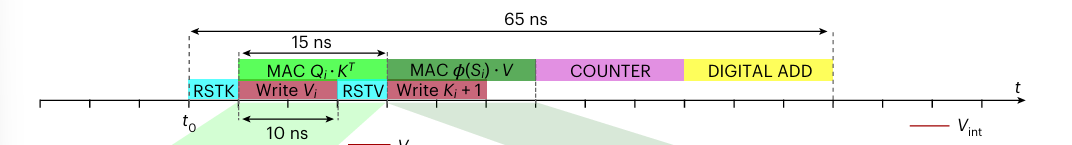

The proposed chip has a set of gain cells to store K and a set of gain cells to store V. There is a fixed number of these cells, so sliding window attention is implemented. In sliding window attention, the outputs for token i can be affected by tokens [i-W, … i-2, i-1, i]. Fig. 2(c) shows how sliding window attention is implemented over time in a ping-pong fashion. While the product involving Q and K is being computed, the capacitors for 1 token worth of V are written. The counter step converts the computed value from analog to digital.

One nice benefit of sliding window attention has to do with refreshing the gain cells. Leakage causes the capacitor in the gain cell to “forget” the value it is storing over time (~5ms). With sliding window attention, there is a limit to the amount of time that a particular value needs to be remembered. If that limit is low enough, then there is no need to refresh gain cells.

Results

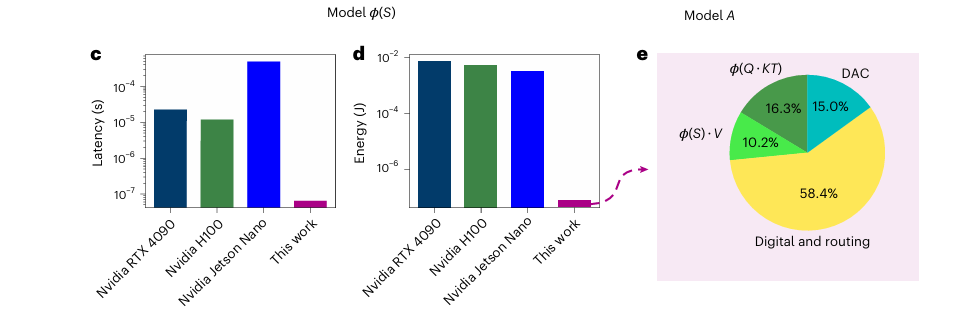

Fig. 5 has the headline results (note the logarithmic scale), these are 100-100,000x improvements in latency and energy:

If you are interested in how this design affects model accuracy, table 1 has the relevant metrics. My takeaway is that it doesn’t seem to have a large effect.

Final Thoughts

Search the web for ‘CMOS full adder’, and you’ll see circuits that seem about as complex as a single gain cell. Those digital circuits only compute a single bit of a sum (and a carry bit as well)! The abstraction of digital logic is an expensive one indeed.

I suppose this is not unlike the Turing Tax associated with higher levels of abstraction.

Fascinating breakdown of the tradeoffs between digital abstraction and analog efficiency. The comparison to a CMOS full adder really drives home the overhead cost. What stood out is how the hard sigmoid constraint actually becomes a design feature rather than a limitation once you factor in the energy savings. I've been folowing similar work on compute-in-memory architectures but the specifics on sliding window attention solving the refresh problem is elegent.