CHERIoT: Complete Memory Safety for Embedded Devices

Hardware support for fine-grained memory protection

CHERIoT: Complete Memory Safety for Embedded Devices Saar Amar, David Chisnall, Tony Chen, Nathaniel Wesley Filardo, Ben Laurie, Kunyan Liu, Robert Norton, Simon W. Moore, Yucong Tao, Robert N. M. Watson, and Hongyan Xia Micro'23

If you are like me, you’ve vaguely heard of CHERI, but never really understood what it is about. Here it is in one sentence: hardware support for memory protection embedded in every single pointer.

This particular paper focuses on CHERI implementation details for embedded/IoT devices.

Capabilities

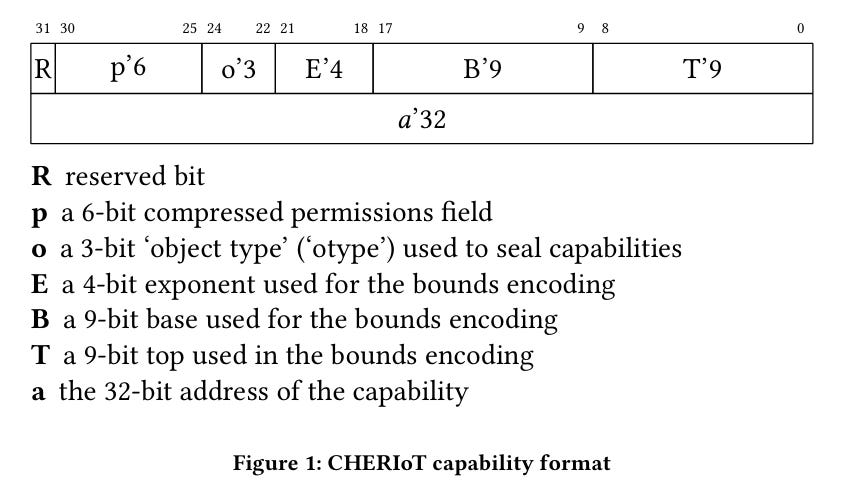

The C in CHERI stands for capability. A capability is a fat pointer which contains an address, bounds, and access permissions. Fig. 1 shows the bit layout (64 bits total) of the capabilities used by CHERIoT:

Here is the fundamental concept to understand: the only way to access memory in a CHERI architecture is via a capability. There are no pointers other than capabilities. The hardware uses special tag bits (associated with registers and memory locations), to track which registers or memory addresses contain valid capabilities, and which do not.

In the following example, u is a regular old integer (the associated tag bit will not be set). p is a pointer generated by reinterpreting the bits in u. The tag bit associated with p will not be set, and thus memory read/writes using p will fail.

uint64_t u = <whatever>;

uint8_t* p = (uint8_t*)&u;

*p = 4; // hardware trap!If a programmer cannot create a capability willy-nilly, where do they come from? At boot, the hardware creates the uber-capability (i.e., one which has full permissions to access all memory) and places this capability into a specific register. The initial OS code that runs on boot can access this capability and can use special instructions to derive new capabilities from it. For example, the OS could derive a capability which has read-only access to the first 1 MiB of memory. The owner of a capability may derive new capabilities from it, but hardware ensures a derived capability cannot have broader permissions than the capability from which it was derived.

Look Ma, no MPU

CHERIoT is designed for embedded use cases, which have real-time requirements. MMUs/MPUs can add variability because they usually contain caches (e.g., TLBs) which have dramatically different performance characteristics in hit vs. miss cases. CHERIoT does away with this. There is no memory translation, and memory protection is supported on a per-capability basis (as opposed to a per-page tracking in the MPU).

This is pretty cool: capabilities not only give fine-grained memory protection, but they also make performance more consistent by removing a cache from the system.

Bounds

Each capability represents a range of memory which can be accessed. Three fields (comprising 22 bits total) in each capability are used to represent the size of memory which is accessible by the capability. The encoding is a bit like floating point, with an exponent field which allows small sizes (i.e., less than 512 bytes) to be represented exactly, while larger sizes require padding.

Heap Revocation

Astute readers will ask themselves: “how does CHERIoT prevent use-after-free bugs? A call to free() must somehow invalidate all capabilities which point at the freed region, correct?”

CHERIoT introduces heap revocation bits. Because the total amount of RAM is often modest in embedded use cases CHERIoT can get away with a dedicated SRAM to hold heap revocation bits. There is 1 revocation bit per 8 bytes of RAM. Most software does not have direct access to these bits, but the heap allocator does.

All revocation bits are initially set to zero. When the heap allocator frees memory, it sets the corresponding bits to one. The hardware uses these bits to prevent capabilities from accessing freed memory. You may think that CHERIoT checks revocation bits on each memory access, but it does not. Instead, the hardware load filter checks the revocation bits when the special “load capability” (clc) instruction is executed. This instruction is used to load a capability from memory into a register. The tag bit associated with the clc destination register is set to one only if the revocation bit associated with the address the capability points to is zero, and the tag bit of the clc source address is one.

The final ingredient in this recipe is akin to garbage collection. CHERIoT supports what I like to think of as a simple garbage collection hardware accelerator called the background pipelined revoker. Software can request this hardware to scan a range of memory. Scanning occurs “in the background” (i.e., in clock cycles where the processor was not accessing memory). The background revoker reuses existing hardware to load each potential capability in the specified memory range, and then store it back. The load operation reads the associated tag bit and revocation bit, while the store operation updates the tag bit. This clears the tag bit for any capability that points to revoked memory.

Once the background revoker has finished scanning all memory, the heap allocator can safely set the revocation bits associated with recently freed allocations back to zero and reuse the memory to satisfy future heap allocations.

Results

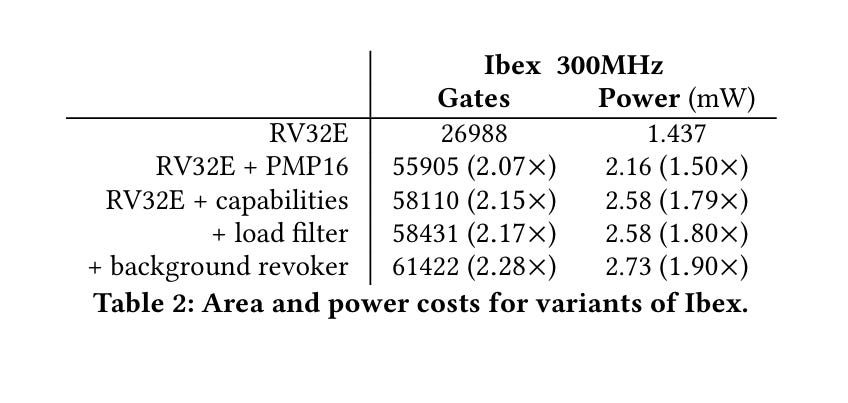

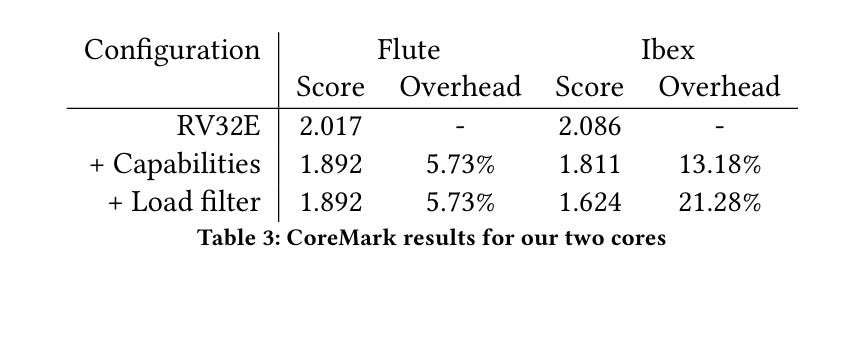

The authors modified two existing processors to support CHERIoT. Flute is a 5-stage processor with a 64-bit memory bus. Ibex is a 2 or 3 stage processor with a 32-bit memory bus.

Table 2 shows the area and power cost associated with extending the Ibex processor to support CHERIoT (roughly 2x for both metrics):

Table 3 uses CoreMark to measure the performance overhead associated with CHERIoT:

Dangling Pointers

I would be interested to know how easily C#/Go/Rust can be modified to use CHERI hardware bounds checking rather than software bounds checking for array accesses. This seems like an area where CHERI could win back some performance.