CHERIoT RTOS: An OS for Fine-Grained Memory-Safe Compartments on Low-Cost Embedded Devices

A modular OS for CHERIoT

CHERIoT RTOS: An OS for Fine-Grained Memory-Safe Compartments on Low-Cost Embedded Devices Saar Amar, Tony Chen, David Chisnall, Nathaniel Wesley Filardo, Ben Laurie, Hugo Lefeuvre, Kunyan Liu, Simon W. Moore, Robert Norton-Wright, Margo Seltzer, Yucong Tao, Robert N. M. Watson, and Hongyan Xia SOSP'25

This paper is a companion to a previous paper which described the CHERIoT hardware architecture. This work presents an OS that doesn’t look like the systems you are used to. The primary goal is memory safety (and security more broadly). Why rewrite your embedded code in Rust when you can switch to a fancy new chip and OS instead?

Capabilities

Recall that a CHERI capability is a pointer augmented with metadata (bounds, access permissions). CHERI allows a more restrictive capability to be derived from a less restrictive one (e.g., reduce the bounds or remove access permissions), but not the other way around.

Compartments

CHERIoT RTOS doesn’t have the notion of a process, instead it has a compartment. A compartment comprises code and compartment-global data. Compartment boundaries are trust boundaries. I think of it like a microkernel operating system. Example compartments in CHERIoT include:

Boot loader

Context switcher

Heap allocator

Thread scheduler

The boot loader is fully trusted and is the first code to run. The hardware provides the boot loader with the ultimate capability. The boot loader then derives more restrictive capabilities, which it passes to other compartments.

You could imagine a driver compartment which is responsible for managing a particular I/O device. The boot loader would provide that compartment with a capability that enables the compartment to access the MMIO registers associated with the device.

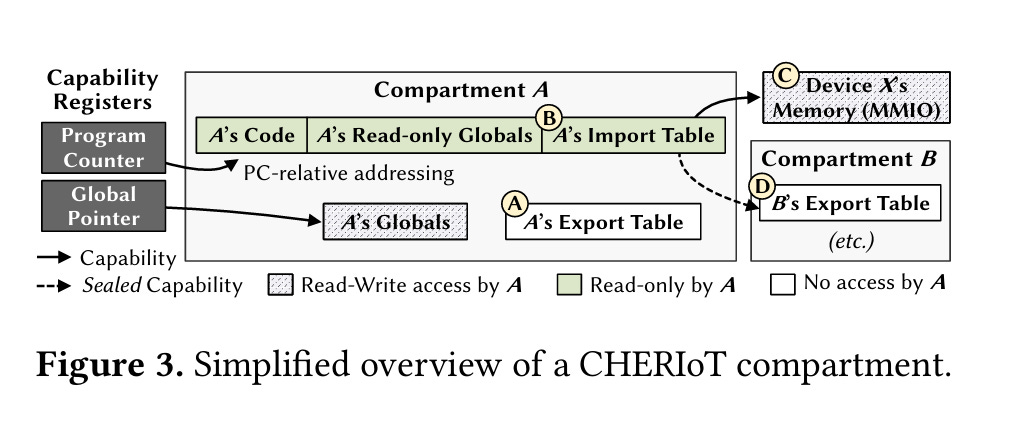

There is no user space/kernel space distinction here, only a set of compartments, each with a unique set of capabilities. Fig. 3 illustrates a compartment:

Sealed Capabilities

The CHERIoT hardware architecture supports sealing of capabilities. Sealing a capability is similar to deriving a more restrictive one, only this time the derived capability is useless until it is unsealed by a compartment which holds a capability with unsealing permissions. I think of this like a client encrypting some data before storing it on a server. The data is useless to everyone except for the client who can decrypt it.

Cross-compartment function calls are similar to system calls and are implemented with sealed capabilities. Say compartment A needs to be able to call a function exported by compartment B. At boot, the boot loader derives a “function call” capability which is a pointer into the export table associated with B, seals that capability, and passes it to compartment A at initialization. The boot loader also gives the switcher a capability which allows it to unseal the function call capability.

When A wants to call the function exported by B, it passes the sealed capability to the switcher. The switcher then unseals the capability and uses it to read metadata about the exported function from B’s export table. The switcher uses this metadata to safely perform the function call.

Capability sealing also simplifies inter-compartment state management. Say compartment C calls into compartment N (for networking) to create a TCP connection. The networking compartment can allocate a complicated tree of objects and then return a sealed capability which points to that tree. Compartment C can hold on to that capability and pass it as a parameter for future networking function calls (which N will unseal and then use). Compartment N doesn’t need to track per-connection objects in its global state.

Heap Allocator

The heap compartment handles memory allocation for all compartments. There is just one address space shared by all compartments, but capabilities make the whole thing safe. As described in the previous summary, when an allocation is freed, the heap allocator sets associated revocation bits to zero. This prevents use-after-free bugs (in conjunction with the CHERIoT hardware load filter).

Similar to garbage collection, freed memory is quarantined (not reused) until a memory sweep completes which ensures that no outstanding valid capabilities are referencing the memory to be reused.

The allocator supports allocation capabilities which can enforce per-compartment quotas.

Threads

If you’ve had enough novelty, you can rest your eyes for a moment. The CHERIoT RTOS supports threads, and they mostly behave like you would expect. The only restriction is that threads are statically declared in code. Threads begin execution in the compartment that declares them, but then threads can execute code in other compartments via cross-compartment calls.

Micro-reboots

Each compartment is responsible for managing its own state with proper error handling. If all else fails, the OS supports micro-reboots, where a single compartment can be reset to a fresh state. The cross-compartment call mechanism supported by the switcher enables the necessary bookkeeping for micro-reboots. The steps to reboot a single compartment are:

Stop new threads from calling into the compartment (these calls fail with an error code)

Fault all threads which are currently executing in the compartment (this will also result in error codes being returned to other compartments)

Release all resources (e.g., heap data) which have been allocated by the compartment

Reset all global variables to their initial state

Dangling Pointers

I wonder how often a micro-reboot of one compartment results in an error code which causes other compartments to micro-reboot. If a call into a compartment which is in the middle of a micro-reboot can fail, then I could see that triggering a cascade of micro-reboots.

The ideas here remind me of Midori, which relied on managed languages rather than hardware support. I wonder which component is better to trust, an SoC or a compiler?