EDM: An Ultra-Low Latency Ethernet Fabric for Memory Disaggregation

Who needs CXL anyways?

EDM: An Ultra-Low Latency Ethernet Fabric for Memory Disaggregation Weigao Su and Vishal Shrivastav ASPLOS'25

This paper describes incremental changes to Ethernet NICs and switches to enable efficient disaggregation of memory without the need for a separate network (e.g., CXL) for memory traffic.

Ethernet Fabric Latency

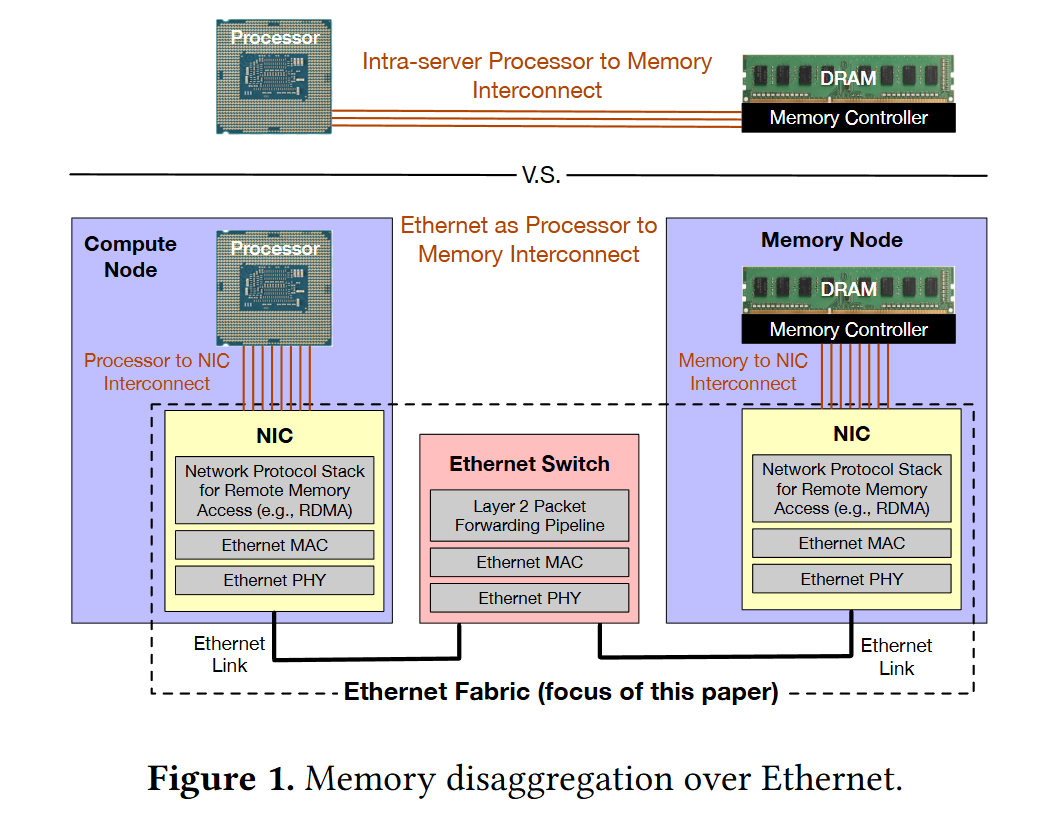

Fig. 1 shows the north star:

Servers are partitioned into Compute Nodes and Memory Nodes. When a compute node wants to access remote memory, it issues a request to its local NIC, which sends the request to the correct memory node (via a switch).

The key problem this paper addresses is Ethernet fabric latency (i.e., the time taken for requests/responses to flow between NICs and switches). The paper assumes that the latency between the processor and the NIC is low (and cites other papers which describe techniques for reducing this latency to below 100ns). Typical Ethernet fabric latency is measured in microseconds, which is much higher than a local memory access.

Ethernet Hardware Stack Changes

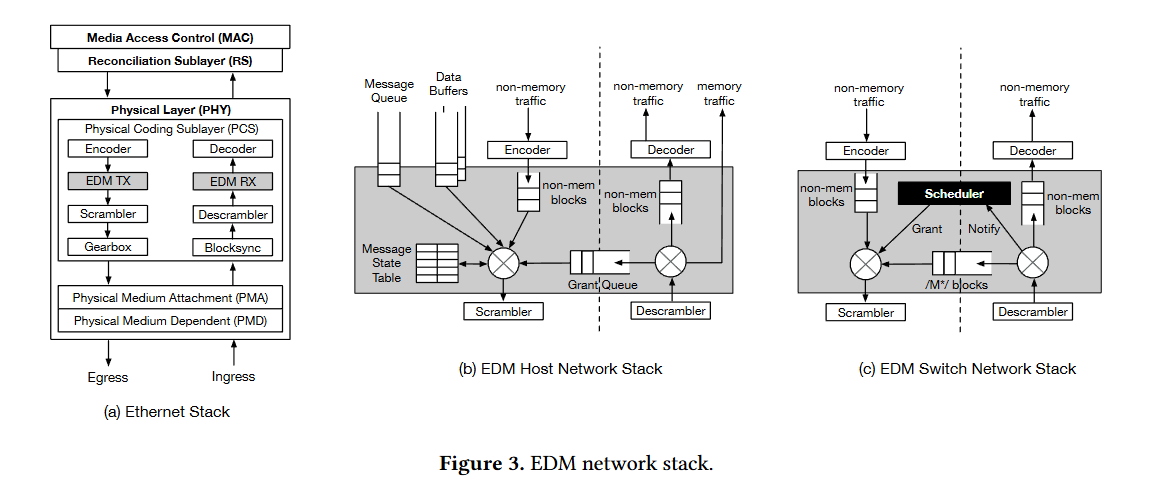

The Ethernet hardware stack can be decomposed into MAC and PHY layers. The MAC is higher level and sits on top of the PHY. The paper proposes implementing EDM (Ethernet Disaggregated Memory) with modifications to the PHY layer in both the NIC and the switch. Normal network packets flow through the MAC and PHY as they usually would, but a side channel exists which allows remote memory accesses to be handled directly by the enhanced PHY layer. Fig. 3 illustrates the hardware changes in Ethernet NICs and switches.

Remote memory access requests and responses are smaller than typical Ethernet packets. Additionally, end-to-end application performance is more sensitive to remote memory access latency than the latency of regular network traffic. The bulk of the paper describes how EDM achieves low latency for remote memory traffic.

Preemption

The EDM PHY modifications allow a memory request to preempt a non-memory packet. Say the MAC sends a 1KiB packet to the PHY, which begins to send the packet over the wire in 66-bit blocks. If a memory request shows up in the middle of transmitting the network packet, the PHY can sneak the memory request onto the wire between 66-bit blocks, rather than waiting for the whole 1KiB to be sent.

Inter-Frame Gap

Standard Ethernet requires 96 bits of zeros to be sent on the wire between each packet. This overhead is small for large packets, but it is non-trivial for small packets (like remote memory access requests). The EDM PHY modifications allow these idle bits to be used for remote memory accesses. The MAC still sees the gaps, but the PHY does not. If you ask an LLM what could possibly go wrong by trying to use the inter-frame gap to send useful data, it will spit out a long list. I can’t find too much detail in the paper about how to ensure that this enhancement is robust. The possible problems are limited to the PHY layer however, as the MAC still sees the zeros it expects.

Scheduling

To avoid congestion and dropping of memory requests, EDM uses an in-network scheduling algorithm somewhat like PFC. The EDM scheduler is in the PHY layer of the switch. Senders notify the switch when they have memory traffic to send, and the switch responds later with a grant, allowing a certain amount of data to be sent.

Results

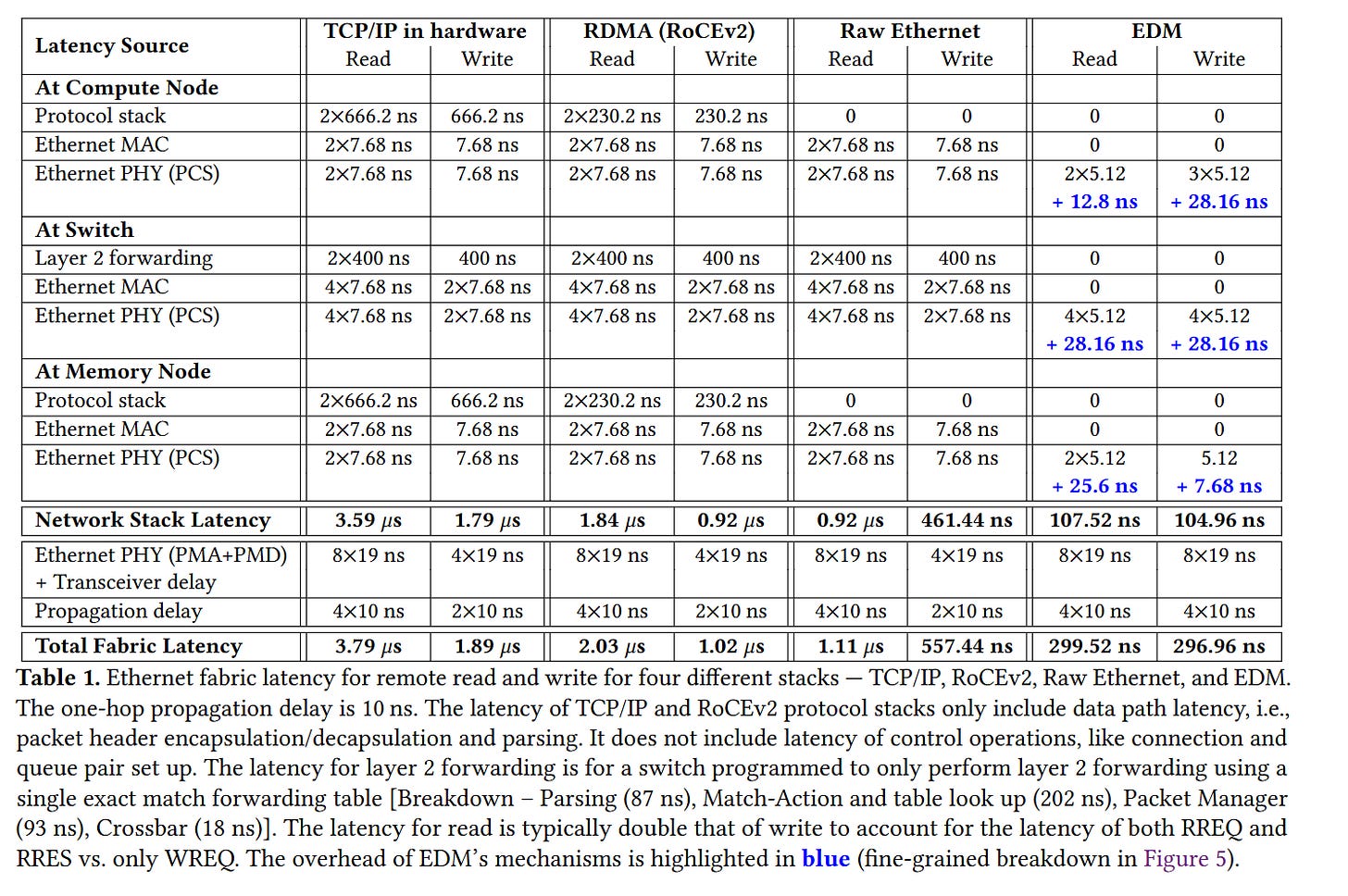

The authors implemented EDM on FPGAs (acting as both NIC and switch). Table 1 compares latencies for TCP/IP, RDMA, raw Ethernet packets, and EDM, breaking down latencies at each step:

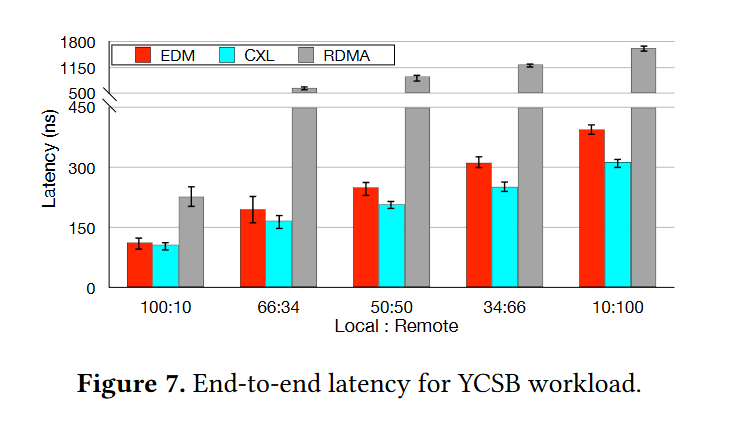

Fig. 7 throws CXL into the mix:

Dangling Pointers

Section 3.3 “Practical Concerns” has a discussion of what could go wrong (e.g., fault tolerance and data corruption). It is hard to judge how much work is needed to make this into something that industry could rely on.