Extended User Interrupts (xUI): Fast and Flexible Notification without Polling

Fast kernel bypass for signals

Extended User Interrupts (xUI): Fast and Flexible Notification without Polling Berk Aydogmus, Linsong Guo, Danial Zuberi, Tal Garfinkel, Dean Tullsen, Amy Ousterhout, and Kazem Taram ASPLOS'25

This paper describes existing hardware support for userspace interrupts, and extensions to make it more efficient.

Yet Another Kernel Bypass

The kernel is powerful, and yet slow. You only want to call on it when necessary. Kernel bypass technologies like DPDK and io_uring exist to allow applications to reduce the frequency of kernel calls.

In addition to I/O, applications frequently call the kernel to communicate between threads. For example, in a producer/consumer design, the producer could use a signal to tell the consumer that more data is ready. Section 2 of the paper reminds readers that each of these signals costs about 2.4 microseconds.

The idea behind userspace interrupts is to get the kernel out of the way and instead have dedicated hardware to support cheap signaling between threads.

Intel UIPI

Architecture

UIPI is a hardware feature introduced by Intel with Sapphire Rapids. Section 3 of the paper describes how UIPI works, including reverse engineering some of the Sapphire Rapids microarchitecture.

Like other kernel bypass technologies, the kernel is still heavily involved in the control path. When a process requests that the kernel configure UIPI, the kernel responds by creating or modifying the user interrupt target table (UITT) for the process. This per-process table has one entry per thread. The kernel thread scheduler updates this table so that the UIPI hardware can determine which core a thread is currently running on.

Once the control path is setup, the data path runs without kernel involvement. Userspace code which wants to send an interrupt to another thread can execute the senduipi instruction. This instruction has one operand, which is an index into the UITT (the index of the destination thread). The hardware then consults the UITT and sends an inter-processor interrupt (IPI) to the core on which the destination thread is running. Userspace code in the destination thread then jumps to a pre-registered interrupt handler, which runs arbitrary code in userspace. Hardware has long supported IPIs, but typically only the kernel has had the ability to invoke them.

The hardware has the ability to coordinate with the OS to handle the case where the destination thread is not currently running on any core. These cases do involve running kernel code, but they are the slow path. The fast path is handled without any kernel involvement.

Microarchitecture

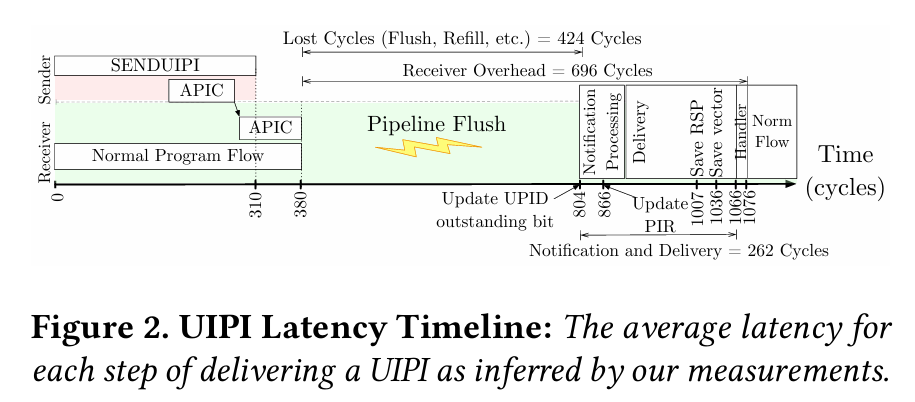

The authors measure an end-to-end latency of 1360 clock cycles for a userspace interrupt on Sapphire Rapids. Fig. 2 illustrates where that time goes:

The largest cost is the pipeline flush when the receiving core receives the IPI. Section 3.4 describes experiments the authors performed to determine these numbers, including how they determined that the receiving processor pipeline is flushed. Note that “flush” here means that in-flight instructions are squashed (i.e., what happens when a branch misprediction is detected). An alternative strategy would be to drain the pipeline, which would let outstanding instructions commit before handling the interrupt. This would avoid duplicate work but would increase the latency of handling an interrupt.

Tracked Interrupts

The authors propose tracked interrupts to solve the performance problem associated with pipeline flushes. When an interrupt is received, the receiving core immediately injects the micro-ops needed to handle the interrupt into the pipeline. Outstanding instructions are not squashed. This may sound similar to draining, but there is a key difference. With draining, the processor waits for all inflight instructions to commit before injecting the interrupt handling micro-ops. With tracked interrupts, micro-ops enter the pipeline immediately, and the out-of-order machinery of the processor will not see any dependencies between the interrupt handling micro-ops and the inflight instructions. This means that the interrupt handling micro-ops can execute quickly and typically do not need to wait behind all inflight instructions.

Results

The paper has simulation results which show that tracked interrupts save 414 clock cycles on the receiver side. The paper also discusses some related improvements to UIPI:

Userspace timer support

Userspace interrupts from I/O devices

Safepoints - to allow userspace interrupts to place nice with garbage collection

Dangling Pointers

I wonder how much of the Sapphire Rapids design was dictated by simplicity (to reduce the risk associated with this feature)?

A frequent theme in papers reviewed on this blog is how difficult it is to implement fine-grained multithreading on general purpose multi-core CPUs. I wonder how much userspace interrupt support can help with that problem?