LoopFrog: In-Core Hint-Based Loop Parallelization

Thread-level Speculation with hints

LoopFrog: In-Core Hint-Based Loop Parallelization Marton Erdos, Utpal Bora, Akshay Bhosale, Bob Lytton, Ali M. Zaidi, Alexandra W. Chadwick, Yuxin Guo, Giacomo Gabrielli, and Timothy M. Jones MICRO'25

Dangling Pointers

To my Kanagawa pals: I think hardware like this would make a great target for Kanagawa, what do you think?

The message of this paper is that there is plenty of loop-level parallelism available which superscalar cores are not yet harvesting.

Diminishing Returns from Out of Order Execution

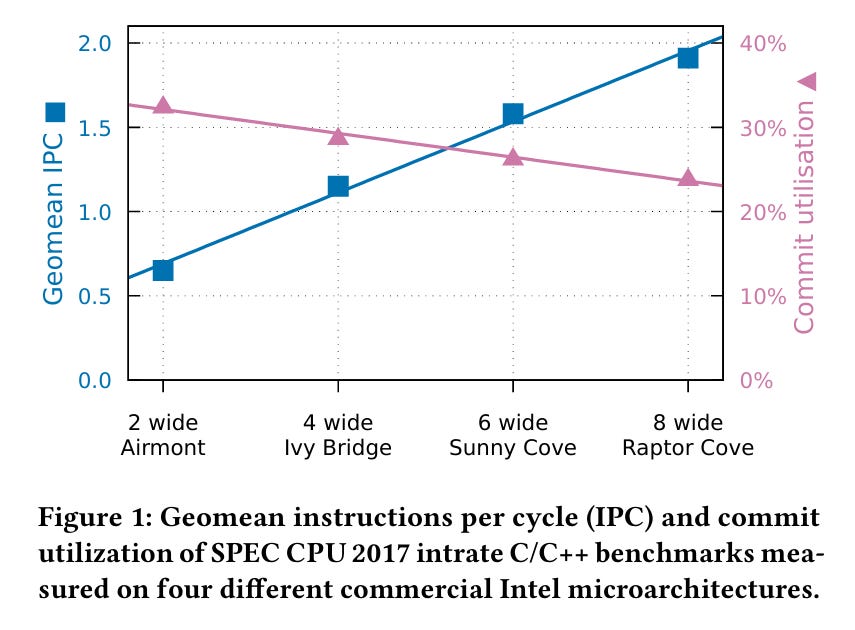

Fig. 1 illustrates the classic motivation for multi-core processors: scaling the processor width by 4x yields a 2x IPC improvement. In general, wider cores are heavily underutilized.

The main idea behind LoopFrog is to add hints to the ISA which allow a wide core to exploit more loop-level parallelism in sequential code.

Structured Loops

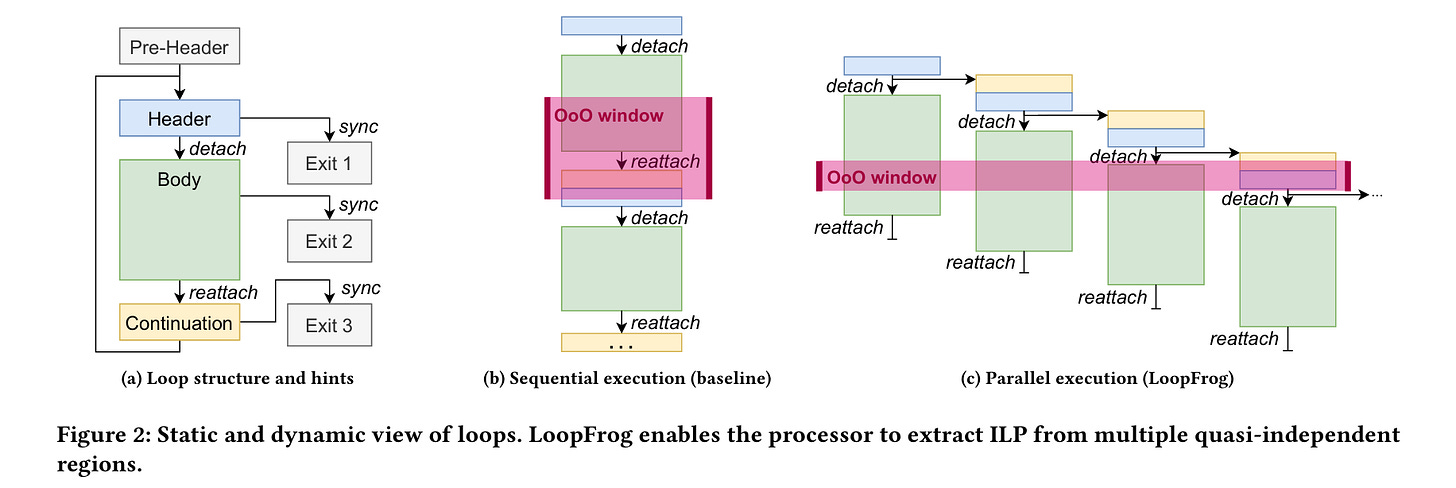

If you understand Fig. 2, then you understand LoopFrog, the rest is just details:

The compiler emits instructions which the processor can use to understand the structure of a loop. Processors are free to ignore the hints. A loop which can be optimized by LoopFrog comprises three sections:

A header, which launches each loop iteration

A body, which accepts values from the header

A continuation, which computes values needed for the next loop iteration (e.g., the value of induction variables).

Each execution of the header launches two threadlets. A threadlet is like a thread but is only ever executed on the core which launched it. One threadlet launched by the header executes the body of the loop. The other threadlet launched by the header is the continuation, which computes values needed for the next loop iteration.

Register loop-carried dependencies are allowed between the header and continuation, but not between body invocations. That is the key which allows multiple bodies to execute in parallel (see Fig. 2c above).

Details

At any one time, there is one architectural threadlet (the oldest one), which can update architectural state. All other threadlets are speculative. Once the architectural threadlet for loop iteration i completes, it hands the baton over to the threadlet executing iteration i+1, which becomes architectural.

Dependencies through memory are handled by the speculative state buffer (SSB). When a speculative threadlet executes a memory store, data is stored in the SSB and actually written to memory later on (i.e., after that threadlet is no longer speculative). Memory loads read from both the L1 cache and the SSB, and then disambiguation hardware determines which data to use and which to ignore.

The hardware implementation evaluated by the paper does not support nested parallelization, it simply ignores hints inside of nested loops.

Results

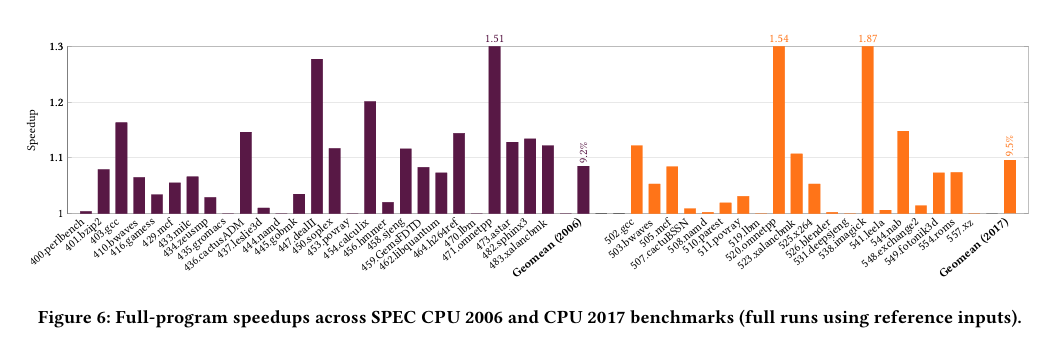

Fig. 6 shows simulated performance results for an 8-wide core. A core which supports 4 threadlets is compared against a baseline which does not implement LoopFrog.

LoopFrog can improve performance by about 10%. Fig. 1 at the top shows that an 8-wide core experiences about 25% utilization, so there may be more fruit left to pick.