SHADOW: Simultaneous Multi-Threading Architecture with Asymmetric Threads

A microarchitecture for fickle workloads

SHADOW: Simultaneous Multi-Threading Architecture with Asymmetric Threads Ishita Chaturvedi, Bhargav Reddy Godala, Abiram Gangavaram, Daniel Flyer, Tyler Sorensen, Tor M. Aamodt, and David I. August MICRO'25

Some processors excel at exploiting instruction level parallelism (ILP), others excel at thread level parallelism (TLP). One approach to dealing with this heterogeneity is to assign each application to a microarchitecture which is suited for it (e.g., OLTP on ILP-optimized processors, OLAP on TLP-optimized processors). The problem is that some applications defy categorization. The characteristics of the workload may flip-flop at high frequency (milliseconds or seconds). This paper proposes a microarchitecture (named SHADOW) that is specialized for these fickle workloads.

Hybrid SMT Core

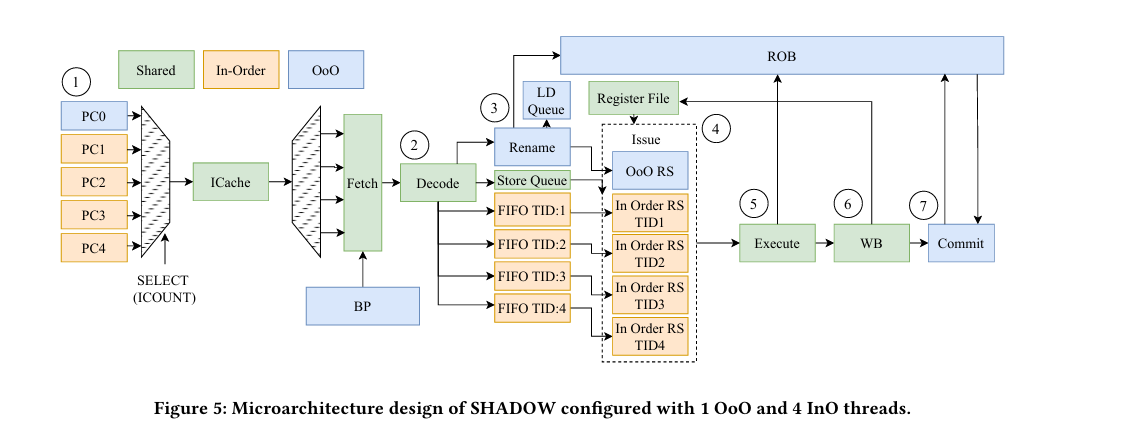

Fig. 5 summarizes the design described in this paper:

This processor exposes five hardware threads. One hardware thread (the Out-of-Order thread, in blue) exploits ILP. The other four threads (In-Order threads, in yellow) exploit TLP. Green components in Fig. 5 are shared between the threads. It may not look like much is shared, but a lot is (e.g., caches, fetch, decode, execute).

The OoO thread has all the bells and whistles you would expect: branch prediction, a reorder buffer, register renaming. The InO threads look more like what you would see on a GPU: no branch prediction, no register renaming.

Most of the pipeline resources are shared between threads with time-division-multiplexing. For example, on each cycle, a single hardware thread accesses the instruction cache.

Software Support

The SHADOW architecture assumes some help from software. The OS can use the shdw_cfg instruction during OS-level context switches to inform hardware about the thread being switched to. For example, the OS can use shdw_cfg to tell the hardware if the thread should be considered InO or OoO. The hardware tracks the number of InO threads actively running and uses that to allocate physical registers to the OoO thread. For example, if no InO threads are running, then the OoO thread can use all physical registers.

The paper advocates for a simple software method for dividing work between OoO and InO threads: work-stealing. If an application has a bunch of parallel work to do, dispatch that work to a pool of threads (consisting of both OoO and InO threads). The idea is that if the workload is OoO friendly (not too many cache misses), then the OoO thread will naturally run faster than the InO threads and thus perform more of the work. The arbiters at each pipeline stage are designed with this policy in mind.

If you are like me, when you read that, you thought “if an application has a bunch of parallel work, then shouldn’t it just use the InO threads?” The answer is “no”. The key point is that OoO can do better for some parallelizable workloads, for example: because it does not require N times the working set in caches.

Results

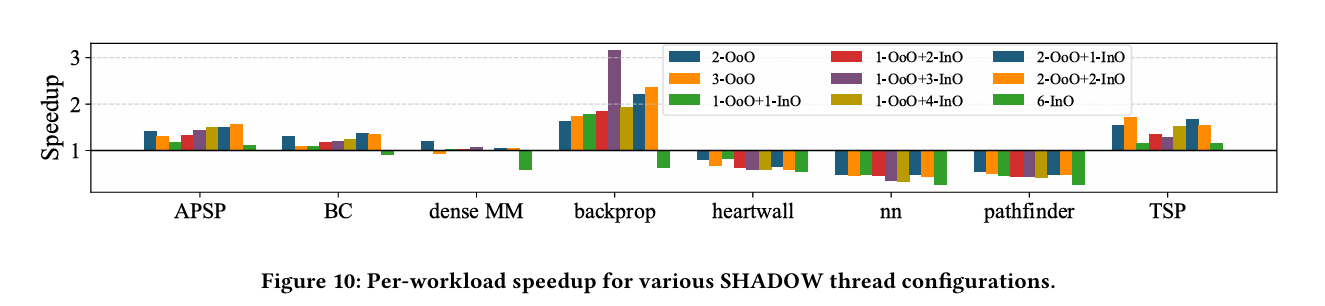

Fig. 10 shows benchmark results for 9 hardware configurations:

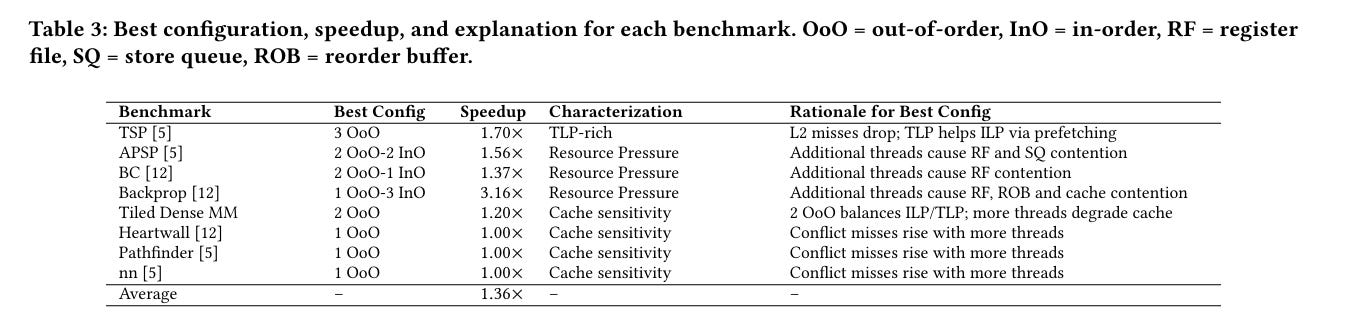

Table 3 adds more color to those results:

The authors estimate that the power and area overhead of adding InO threads to an existing out-of-order core is about 1%. Wowzers those are some inexpensive threads. I imagine the engineering/validation costs are a bigger concern.

Dangling Pointers

The proposed software parallelization model assumes that running N threads multiplies the working set by N, which is true for most parallelization schemes. Pipeline parallelism doesn’t have this property. Maybe everything looks like a nail to me, but pipeline parallelism on CPUs seems to be an under-researched topic.