Dynamic Load Balancer in Intel Xeon Scalable Processor

One way to enable achieve many-core packet processing

Dynamic Load Balancer in Intel Xeon Scalable Processor: Performance Analyses, Enhancements, and Guidelines Jiaqi Lou, Srikar Vanavasam, Yifan Yuan, Ren Wang, and Nam Sung Kim ISCA'25

The Problem

This paper describes the DLB accelerator present in modern Xeon CPUs. The DLB addresses a similar problem discussed in the state-compute replication paper: how to parallelize packet processing when RSS (static NIC-based load balancing) is insufficient.

Imagine a 100 Gbps NIC is receiving a steady stream of 64B packets and sending them to the host. If RSS is inappropriate for the application, then another parallelization strategy would be for a single CPU core to distribute incoming packets to all of the others. To keep up, that load-distribution core would have to be able to process 200M packets per second, but state-of-the-art results top out at 30M packets per second.

Dynamic Load Balancing Hardware

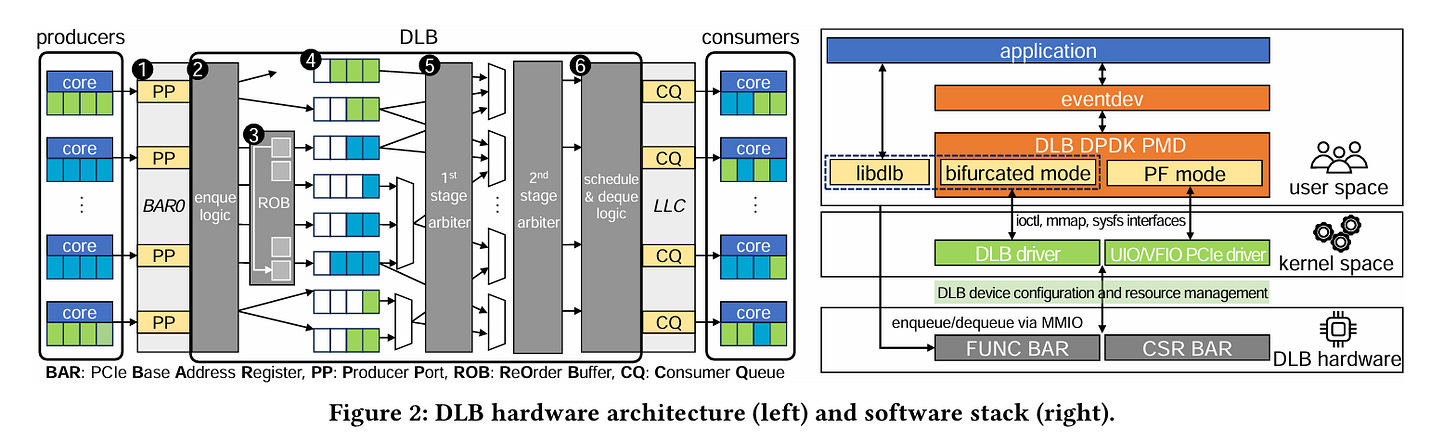

The DLB is an accelerator designed to solve this problem. Fig. 2 illustrates the DLB hardware and software architecture:

A set of producer cores can write 16B queue elements (QEs) into a set of producer ports (PPs). In a networking application, one QE could map to a single packet. A set of consumer cores can read QEs out of consumer queues (CQs).

QEs contain metadata which producers can set to enable ordering within a flow/connection, and to control relative priorities. The DLB balances the load at each consumer, while honoring ordering constraints and priorities.

A set of cores can send QEs to the DLB in parallel without suffering too much from skew. For example, imagine a CPU with 128 cores. If DLB is not used, and instead RSS is configured to statically distribute connections among those 128 cores, then skew could be a big problem. If DLB is used, and there are 4 cores which write into the producer ports, then RSS can be configured to statically distribute connections among those 4 cores, and skew is much less likely to be a problem.

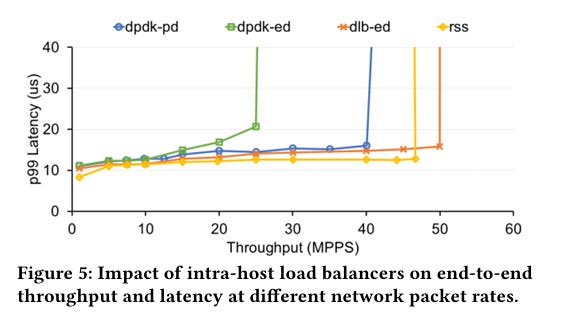

Fig. 5 shows that DLB works pretty well. dpdk-pd and dpdk-ed are software load balancers, while dlb-ed uses the DLB accelerator. DLB offers similar throughput and latency to RSS, but with much more flexibility.

AccDirect

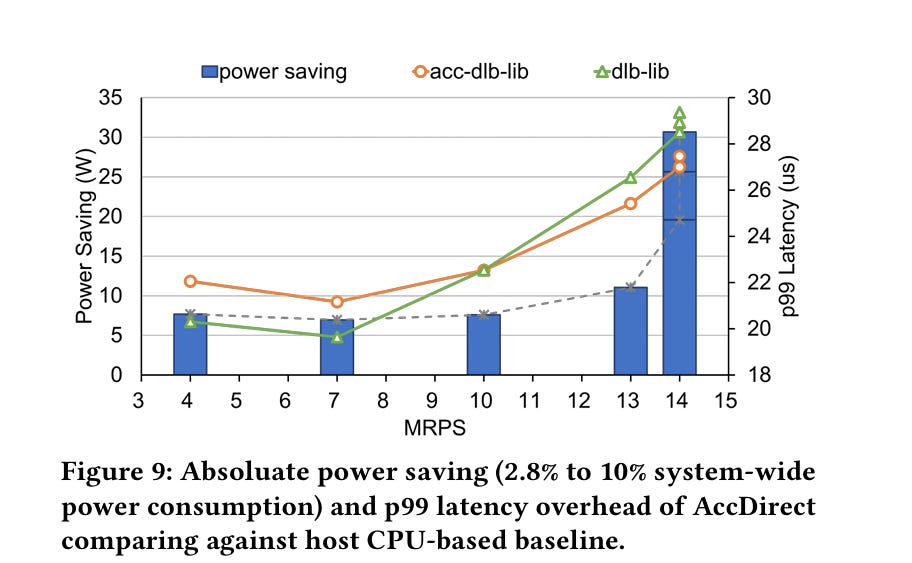

One awkward point in the design above is the large number of CPU cycles consumed by the set of producer cores which write QEs into the DLB. The paper proposes AccDirect to solve this. The idea is that DLB appears as a PCIe device, and therefore a flexible NIC can use PCIe peer-to-peer writes to send packets directly to the DLB. The authors find that the NVIDIA BlueField-3 has enough programmability to support this. Fig. 9 show that this results in a significant power savings, but not too much of a latency improvement:

Dangling Pointers

I feel like it is common knowledge that fine-grained parallelism doesn’t work well on multi-core CPUs. In the context of this paper, the implication is that it is infeasible to write a multi-core packet processor that primarily uses pipeline parallelism. Back-of-the-envelope: at 400Gbps, and 64B packets, there is a budget of about 40 8-wide SIMD instructions to process a batch of 8 packets. If there are 128 cores, then maybe the aggregate budget is 4K instructions per batch of 8 packets across all cores. This doesn’t seem implausible to me.

The AccDirect optimization is clever becuase it eliminates the producer core bottleneck by moving packet enqueuing offto the NIC entirely. The power savings make sense, but I'm surprised the latency improvement is so modest given that you're cutting out multiple hops through CPU memory. Maybe the PCIe peer-to-peer write latency is eating most of those gains? Also wondering how this scales with multiple producer NICs all trying to write to DLB simultaneously.

Nice summary! was just reading the paper today, gon try recreate it on my server env.