Light-weight Cache Replacement for Instruction Heavy Workloads

A simple policy that is better than LRU

Light-weight Cache Replacement for Instruction Heavy Workloads Saba Mostofi, Setu Gupta, Ahmad Hassani, Krishnam Tibrewala, Elvira Teran, Paul V. Gratz, and Daniel A. Jiménez ISCA'25

Caches with LRU policies are great, unless the working set exceeds the cache size (e.g., in RTL simulation). This paper describes a simple cache replacement policy (PACIPV) which outperforms LRU in situations where the working set can be thought of as two separate sets of data:

One set is accessed in a round-robin fashion, and is larger than the cache

The other set is accessed in a more random fashion, and/or is smaller than the cache

IPVs and RRPVs

The findings of the paper can be boiled down to two insertion/promotion vectors (IPVs) which describe the cache replacement policy. The paper assumes a 4-way set associative cache and finds IPVs which work in that case, but the technique generalizes.

The cache tracks two bits of metadata for each cache line. These two bits define the re-reference prediction value (RRPV) for a cache line. A low RRPV (e.g., 0 or 1) indicates that the cache line will likely be referenced again before it is evicted. A high RRPV (e.g., 2 or 3) indicates that the cache line is unlikely to be referenced again before it is evicted.

When the cache needs to evict a line from a particular set, it examines the RRPVs associated with each cache line. If any cache line has an RRPV of 3, then it can be evicted. If all RRPVs in the set are less than 3, then all RRPVs are repeatedly incremented (i.e., they move closer to 3) until at least one unlucky cache line has an RRPV of 3 and is chosen for eviction.

An IPV defines a state machine which is responsible for updating RRPVs on cache insertion and cache hit events. An IPV comprises five integers (e.g., [0, 1, 1, 2, 2]). The last integer in the list defines the RRPV assigned to a cache line when it is inserted into the cache. The remaining four integers define how RRPVs are updated on each cache hit.

Symbolically, if the IPV is: [A, B, C, D, E], then the RRPV associated with a newly inserted cache line is E. If a cache hit occurs on a cache line with an RRPV of 3, then the RRPV of that line is updated to be D. Similarly, if a hit occurs on a cache line with an RRPV of 1, then the new RRPV is set to B.

RRPVs are dynamically tracked by the hardware on a per-cache line basis. RRPVs only apply to cache lines which are present in a cache; they are forgotten when a cache line is evicted.

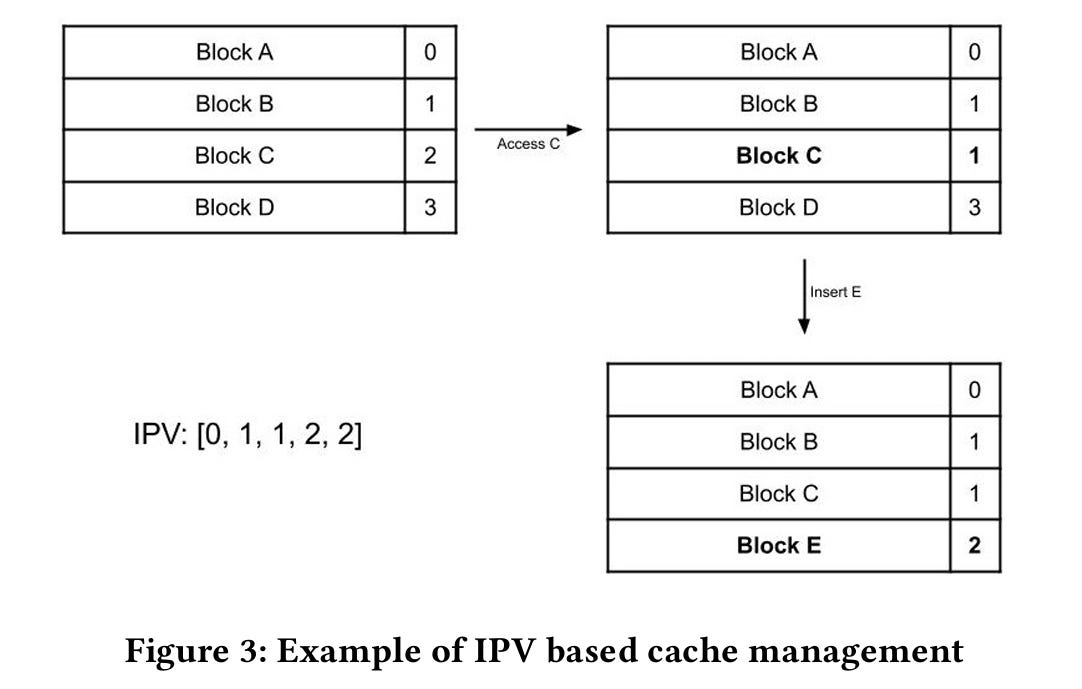

Fig. 3 shows an example IPV ([0, 1, 1, 2, 2]) and two state transitions. Initially, the RRPV of cache line A is 0, while the RRPV of cache line B is 1, etc. The RRPV associated with C is updated when C is accessed. Because C has an RRPV of 2 at the time of the access, the new RRPV is 1 (e.g., the bold element in the IPV: [0, 1, 1, 2, 2]). Next, E is inserted into the cache. Cache line D is selected to be evicted because it has an RRPV of 3 (recall that only cache lines with RRPV=3 can be evicted). The RRPV associated with cache line E is initialized to 2 (the last number in the IPV).

Prefetch IPV

A cache policy is defined by two IPVs. One IPV determines how RRPVs are updated when a demand access (e.g., a load or store instruction) occurs. The other IPV defines how RRPVs are updated when a prefetch occurs. I assume this applies to both hardware and software prefetching.

Magic Values

Section 4 of the paper describes how many candidate IPVs were evaluated under simulation. The best general-purpose IPVs are:

[0, 1, 1, 0, 3](demand accesses)[0, 1, 0, 0, 3](prefetch accesses)

The way I think of this is that cache lines are initially placed into the cache “under suspicion” (RRPV=3). This means that the cache policy does not have high confidence that a cache line will be referenced a second time. If it is referenced a second time however, then the cache line becomes the teacher’s pet and is promoted all the way to RRPV=0. It is hard to stay the teacher’s pet for a long time. If any eviction occurs and no other line has an RRPV=3, then the cache line will be downgraded to RRPV=1. RRPV=1 is fairly sticky however, because accesses at RRPV=1 or RRPV=2 will reset the RRPV to 1.

The prefetch IPV is similar to the demand IPV. The critical difference is that the prefetch policy is more forgiving to cache lines at RRPV=2, they will be promoted all the way back to RRPV=0 on a prefetch access.

The authors also found an IPV pair which works better for data-heavy workloads, it is:

[0, 0, 0, 1, 3](demand accesses)[0, 0, 1, 1, 3](prefetch accesses)

Results

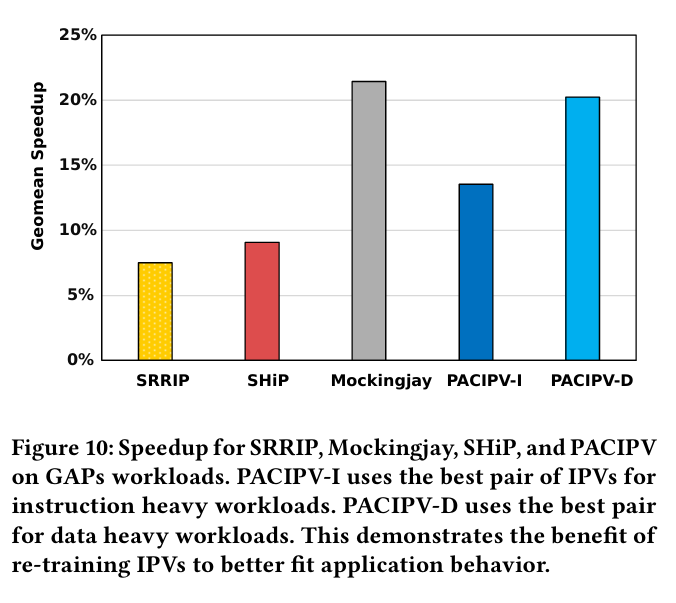

Fig. 10 shows benchmark results for both IPV pairs described above against state-of-the-art cache replacement policies. PACIPV-D is the IPV pair which is better suited for data-heavy workloads. There is some overfitting as PACIPV-D was trained on the benchmarks measured here.

Dangling Pointers

I wonder if there is value in storing RRPVs in DRAM. Kind of like how additional DRAM bits are used for ECC data. This would allow the cache to remember properties of a cache line over long periods of time.