Rearchitecting the Thread Model of In-Memory Key-Value Stores with μTPS

Pipeline parallelism for better cache locality

Rearchitecting the Thread Model of In-Memory Key-Value Stores with μTPS Youmin Chen, Jiwu Shu, Yanyan Shen, Linpeng Huang, and Hong Mei SOSP'25

I love this paper, because it grinds one of my axes: efficient pipeline parallelism on general purpose CPUs. In many hardware designs, pipeline parallelism is the dominant form of parallelism, whereas data parallelism takes the cake on CPUs and GPUs. It has always seemed to me that there are applications where pipeline parallelism should be great on multi-core CPUs, and here is an example.

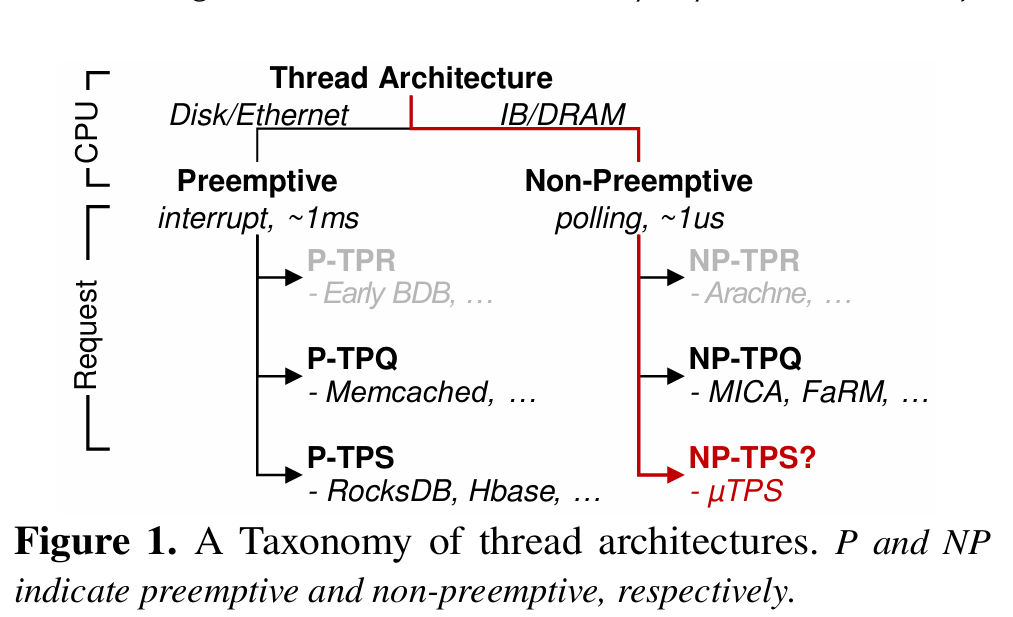

Key-Value Store Taxonomy

Fig. 1 illustrates the design space for key-value stores:

One axis is preemptive vs non-preemptive (cooperative) multi-threading. Preemptive multithreading involves context switches, which are cheap relative to disk reads but expensive relative to DRAM reads.

The other axis is how to assign work to threads. Thread per request (TPR) creates a new thread for each request. This approach has been subsumed by thread per queue (TPQ), which uses a static number of threads, each of which dequeues requests from a dedicated queue and executes all of the work for a single request to completion. Finally, there is thread per stage (TPS), which divides the steps necessary to complete a request into multiple pipeline stages, and then divides the pipeline stages among a set of threads. The work discussed here uses a non-preemptive, thread per stage architecture.

Pipelining Advantages

A pipelined implementation seems more complicated than an imperative run-to-completion design, so why do it? The key reason is to take advantage of the CPU cache. Here are two examples:

As we’ve seen in other networking papers, a well-designed system can leverage DDIO to allow the NIC to write network packets into the LLC where they are then consumed by software.

Key-value stores frequently have hot tuples, and there are advantages to caching these (example here).

It is hard to effectively cache data in a TPR/TPQ model, because each request runs the entire key-value store request code path. For example, a CPU core may have enough cache capacity to hold network buffers or hot tuples, but not both.

Pipelining Disadvantages

The key disadvantage to a TPS architecture is load balancing. One stage could become the bottleneck, leaving CPU cores idle. The authors propose dynamic reconfiguration of the pipeline based on workload changes.

Another challenge with pipelining is implementing efficient communication between cores, because data associated with each request flows down the pipeline with the request itself.

Architecture

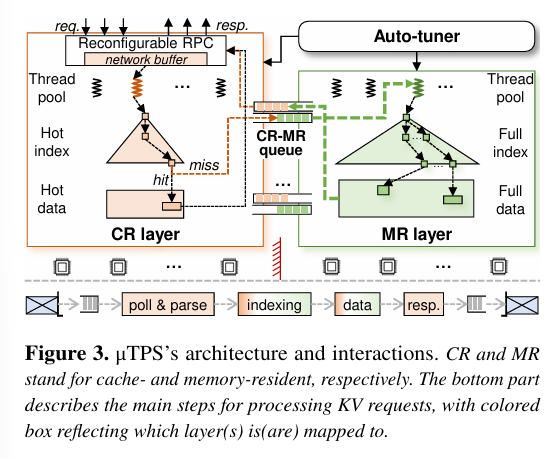

Fig. 3 shows the pipeline proposed in this paper:

The NIC writes request packets into the network buffer (stored in the LLC). The cache-resident layer reads data from this buffer and handles requests involving commonly used keys by accessing the hot index and hot data caches (also in the LLC).

The memory-resident layer handles cold keys and values, which are stored in DRAM.

One set of threads (pinned to CPU cores) implement the cache-resident layer, and a different set of threads (pinned to other CPU cores) implement the memory-resident layer. An auto-tuner continually monitors the system and adjusts the number of threads assigned to each layer. Section 3.5 describes the synchronization required to implement this adjustment.

Cache-Resident Layer

The NIC writes request packets into a single queue. The cache-resident threads cooperatively read requests from this queue. If there are N threads in the pool, then thread i reads all requests with: i == request_slot % N.

Next, threads check to see if the key associated with a request is hot (and thus cached in the LLC). Time is divided into epochs. During a given epoch, the set of cached items does not change. This enables fast lookups without costly synchronization between threads. A background thread gathers statistics to determine the set of items to be cached in the next epoch and has the ability to atomically switch to the next epoch when the time comes. The number of hot keys is kept small enough that it is highly likely that hot keys will be stored in the LLC.

Requests that miss in the cache-resident layer are passed on to the memory-resident layer for further processing (via the CR-MR queue).

Typically, the LLC is treated like a global resource (shared by all cores). But this particular use case requires that most of the LLC be dedicated to the cache-resident layer. This is accomplished with the help of the PQOS utility from Intel, which uses “Intel(R) Resource Director Technology” to control which ways of the LLC are assigned to each layer.

Memory-Resident Layer

The memory-resident layer operates on batches of requests. Because the requests are not hot, it is highly likely that each request will require DRAM accesses for index lookups (keys) and data lookups (values). Software prefetching is used to hide DRAM latency during index lookups. When servicing get operations, data values are copied directly into the outgoing network buffer.

CR-MR Queue

The CR-MR queue is used to communicate between the two layers. Each (CR thread, MR thread) pair has a dedicated lock-free queue. Enqueue operations use a round-robin policy (message N from CR thread C is sent to MR thread: N % Num_MR_Threads). Dequeue operations must potentially scan queues corresponding to all possible senders. Multiple requests can be stored per message, to amortize control overhead.

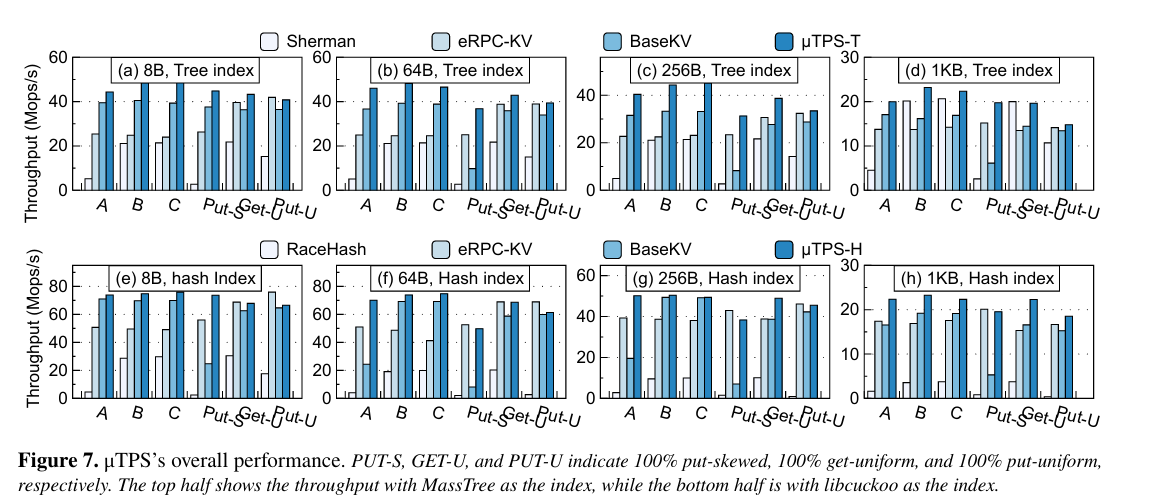

Results

Fig. 7 has throughput results for synthetic workloads (A, B, and C have different ratios of put/get operations), uTPS-T is this work:

Dangling Pointers

The pipelining here is coarse-grained, and the design is only optimized for the LLC. I wonder if a more fine-grained pipeline would allow hot data to be stored in L2 caches. For example, the set of hot keys could be sharded among N cores, with each core holding a different shard in its L2 cache.

It seems redundant that this design requires software to determine the set of hot keys, when the hardware cache circuitry already has support to do something like this.

Really smart application of pipeline parallelism here. The cache-resident vs memory-resident split makes sense giventhe performance gap between LLC and DRAM. I'm curious tho if the auto-tuner logic creates any thrashing when workloads shift between hot and cold key distributions unexpectadly.